Waterford has a long association with Bristol. Following the arrival of Henry II to Waterford in 1171 the harbor area was carved up by merchants, knights and religious, many with a connection to the inland port of Bristol in SW England. The city developed on a point where the rivers Avon and Frome met, a convenient crossing place at the furthest point inland that ships could reach by drifting on the tidal current. For centuries, trade flowed between the two areas depending on the vagaries of wind and tide and whatever luck might come a sailor’s way. But the arrival of steam power altered the relationship forever. As ships became faster, bigger and more reliable, change was required to facilitate the transition. This paper will look at the ships that changed it.

In September 1823 a paddle steamer called the Duke of Lancaster (1822) was advertised for a round trip to Ireland. Departing Bristol every Tuesday, it would call first to Tenby and then Waterford where it would depart on Fridays. The advert assures that the packet is built on the most improved principles, with powerful machinery and elegant accommodations which are attended to by male and female stewards for every convenience.[i] It must not have taken off, however, as there appear to be no more advertisements for the craft, and no details of arrivals or departures in the Waterford papers that I can find.

Three years elapsed before a regular steamer commenced on the route. That was the Nora Creina(1826) 202 tons and launched on the 22nd July from William Seddon & Co., at North Birkenhead. She commenced in Dec 1926 under captain John Stacey. In a year she completed 52 weekly round trip voyages. A loyal and trustworthy craft, she remained on the route until 1846.[ii]

According to the Waterford Mail, the Nora Creina departed Passage on the 8th December for Bristol with a cargo of bacon, butter, wheat, oats and flour. It’s the earliest I can find of her leaving Waterford, perhaps her maiden, outbound voyage.[iii]

In June of 1827 business was on the up and a second service was added. This was the Palmerston (1823),which was operating from Bristol and was brought on to provide cover it seems. An advertisement for the Waterford and Bristol Steam Navigation Company would run the Palmerston every Tuesday to Bristol , returning Fridays. She would carry passengers, carraiges and horses only. Meanwhile the Nora Creina would run to Bristol on a Saturday and return from Bristol on Wednesday, with goods and passengers. John Bogan at Adelphi, Waterford was the local agent, Robert Smart at the Quay, Bristol performed services on the English side.[iv]

Norah Creina as depicted on Leahy’s Map of Waterford 1836

The appropriately named City of Waterford was launched on 24th February 1829. Built at the War Office Company yard, Bristol, she was 272 tons and was jointly owned by merchants of both cities including JD Lapham. The vessel commenced on the route on May 2nd that year under Captain William Bailey.[v]

A local advertisement stated that the new vessel would run to Bristol every Wednesday, returning Saturday. The intended cargo was passengers, goods and cattle. The Nora Creina would sail for Bristol on Saturday’s and return on Wednesdays.[vi]

Over the winter of 1831-32 Killarney (1830) ran with the Nora Creina while the City of Waterford was overhauled, and in May 1833 a new vessel the Water Witch commenced under Captain Stacey. Tragically, the new vessel was lost on the Wexford coast in December that same year. Four passengers and four crew lost their lives.[vii] It wasn’t the only loss that year however, the City of Waterford was chartered for a run to Lisbon and went ashore at Peniche, Portugal and became a total wreck.[viii]

1833 was an unlucky year perhaps. In June another vessel came on the run, the City of Bristol. She was later wrecked in Rhossily Bay on the Severn Sea, a story we have featured before[ix]

In October 1834 a new vessel was added to the fleet of the Waterford and Bristol Steam Navigation Company, the Mermaid. Built in Russell’s yard North Birkenhead, 258 tons and fitted with two 90hp engines, she commenced running on the route in early 1835 under Captain J Hearne. By April she was in difficulty however. Having overtaken a local steamer in the Avon which was grounded and damaged, months of recriminations followed. She moved to the Liverpool run and although she was used on the Waterford run subsequently, she was later lost on a Waterford Liverpool run in 1845.[x]

In 1836 the company operating on the route became the Waterford Commercial Steam Navigation Company[xi] and a very influential name was amongst the shareholders – Malcomson. Both the Norah Creina and Mermaid were transferred to the new company.[xii] One of their first challenges seems to have been a rival service established by Sir John Tobin which saw the Gipsy(1828) and St Patrick(1832) run against the company. The competition lasted almost a year before the ships along with another named William Penn(1833) were bought by the Waterford company.[xiii]

Nora Creina retired in 1846 and was replaced by the Victory (1832) which was lost at the Barrel Rock, Wexford on September 28th 1850 without the loss of life. Her skipper at the time was John Stacey – possibly a son of the previous gentleman.[xiv] Camilla(1844) was a relief ship on the route and became a regular between the period of 1854 – 60.[xv]

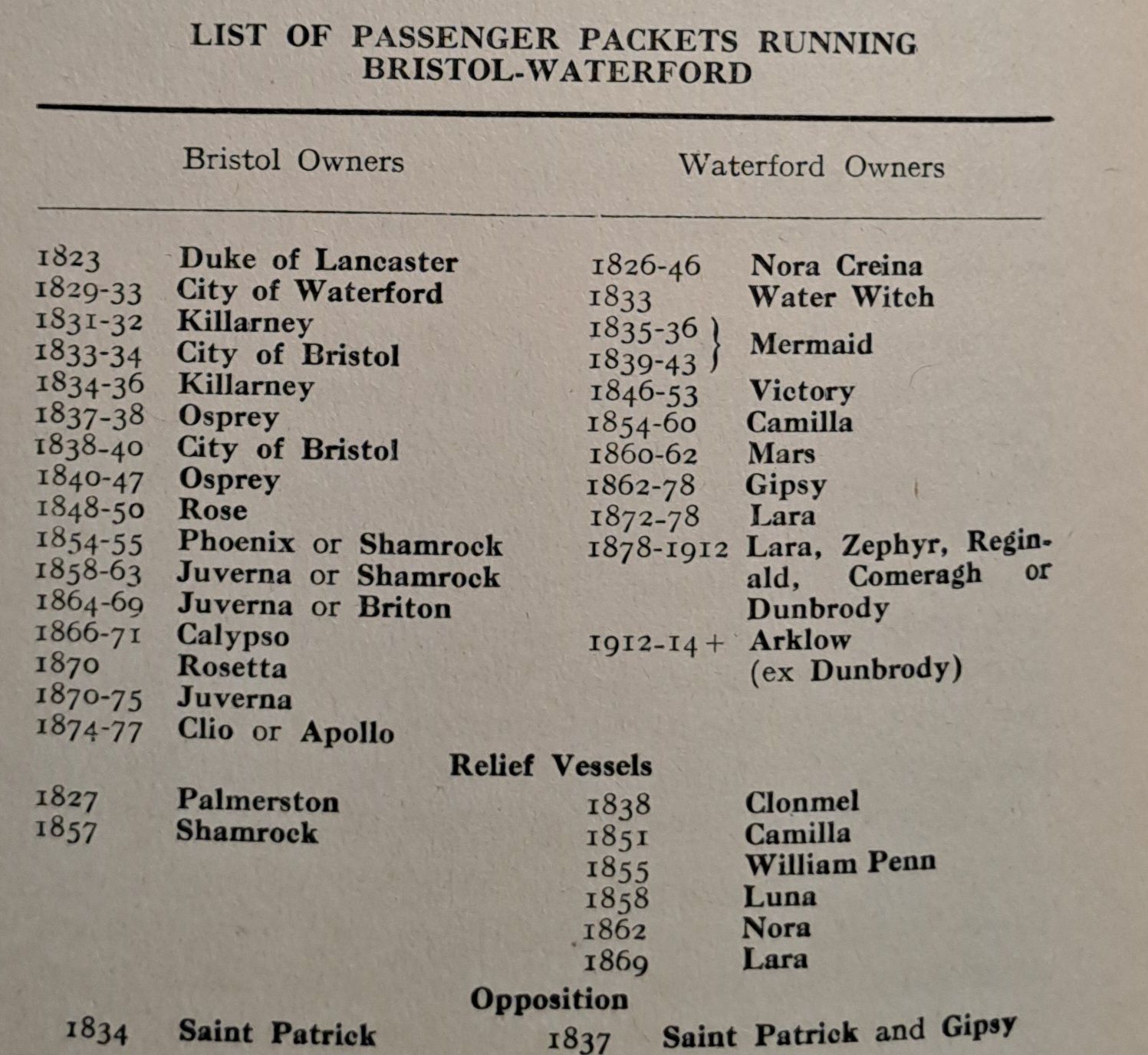

A list of steam vessels that operated on the route – after Grahame Farr

Another ship purpose built for the route was the Mars(1849) built at Malcomson’s Neptune shipyard at the Park Road, Waterford. She was 548 tons and originally launched as a paddle steamer, but was altered to a screw steamer in 1850. She was lost at Linney Head, near Milford on April 1st 1862 on her regular passage from Waterford – Bristol. It’s estimated that 50 died in the tragedy, compounded by the fact that when she struck she was sailing with almost all sail set in a strong gale and thick fog.[xvi]

Another vessel that came to a sticky end was the Gipsy(1859). Built at the Malcomson yard she was 691 tons and an iron screw steamer. She could carry 229 people in winter, 330 in summer. She met her fate on a night sailing from Bristol to Waterford. On Sunday May 12th 1878 she struck a bank on the Avon. All passengers were safely got off, but the next tide moved the vessel across the river and on an ebbing tide, the back of the ship broke making her a total loss. It would take several weeks, tons of dynamite and a party of Royal Navy torpedo men and Royal Engineers to blow the area of the river clear of the ship to allow the River Avon reopen.[xvii]

From 1878 a number of vessels were employed regularly on the route including the Lara(1868), Zephyr(1860), Reginald (1878) and her sister ship Comeragh(1879). The Dunbrody(1886) also grounded in the Avon but with less serious consequences. This time, dynamite was put under the rock that her bow was wedged on. The plan worked – somewhat, she slid into deeper water, and sank – but was salvaged. These ships ran twice a week and the average passage was 15 hours.[xviii]

SS Dunbrody, aground on the Avon Dec 23rd 1896

In July 1912 Clyde Shipping bought out the remainder of the business to Bristol and took possession of Reginald and Dunbrody. The former was sold to the Admiralty in 1914 and became a block ship at Scapa Flow in 1915. The Dunbrody was renamed Arklow and ran up to 1931.

Trade between Waterford and Bristol struggled after WWI – the passenger trade slowed and an embargo on Irish cattle also impacted the service. From local newspaper adverts it seems a service was occasionally run during the 1930s but it appears to have completely halted by the Second World War. The last Clyde company ships to ply the route from Waterford was the Skerries (1921) and occassionally the Rockabill (1931). The last mention I can find for the route was August 1939 when the latter vessel was in Bristol.

By the outbreak of WWII trade between these two maritime trading partners seems to have ceased. If there was any grand announcement, any marking of the occasion or public event to underline the historical sundering of the route, it seems to have gone unreported. Ironic – a route born of a momentous event in Irish history that would shape Irish history for 800 years, should seemingly fade without remark.

Tides & Tales

Much of this article is based on the original work of Farr, Grahame E. West Country Passenger Steamers. 1956. Richard Tilling. London and newspaper reportage. A much more extensive 3,600-word report is now available on our shop. It can be accessed for €2.49 – all funds raised contribute to the ongoing running of the project.

We are a community-based initiative, created with passion, sustained by curiosity, and kept afloat by the generosity of people like you. If Tides and Tales has informed, inspired, or simply entertained you, there are several meaningful ways you can help us continue our work.

- Share this story with a friend, family member, or colleague.

- Leave a comment with feedback.

- Subscribe below to stay connected with our latest content.

- Other ways to assist financially if you can, include;

Donate—even a small contribution helps us keep the stories flowing.

Visit our shop and consider a purchase; all proceeds directly support the project.

Every positive action, big or small, helps us to keep Waterford Harbour’s rich maritime legacy alive and accessible for generations to come. Thank you for being part of the journey.

Andrew,

As per usual, this was a great blog. You are one of the few if not the only one who keeps informing us of our immense mercantile and marine heritage. The South East punched way above it’s weight in enterprise since the early 1700’s. How they continually came up with new ventures when so many ships were wrecked on both coasts. No wonder the South Wexford coast was known as “The graveyard of 1000 ships.”

Keep up the good work

Fascinating article and full of details. Thank you!